“No good deed goes unpunished.” That famous saying applies to a lot of things – including government efforts to do good. There always seem to be unintended consequences.

For example, The Wall Street Journal editors tell us about an obscure government program called the 340B drug program. “The 340B program is a classic example of a well-intended policy that has caused unintended harm. Congress established the program in 1992 to help hospitals that disproportionately serve Medicaid and low-income patients. Such hospitals are allowed to buy outpatient drugs at steeply discounted rates, on average about 45% of a drug’s list price.”

Hospitals then charge insurers and Medicare a large mark-up on the drugs when their pharmacies administer them to patients, pocketing the difference. Spending in the program has surged 11-fold since 2010 and exceeds Medicaid pharmaceutical spending.

One culprit is ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion, which made more hospitals eligible. Some 2,700 hospitals now qualify for discounts, up from 45 in 1992. These include such well-off hospitals as the Cleveland Clinic, New York’s Northwell Health system, Beverly Hills’s Cedars-Sinai and New York Presbyterian.

As the Congressional Budget Office explained recently in a report, the program has encouraged consolidation among providers since outpatient clinics and physicians owned by eligible hospitals benefit from discounts. So do pharmacies, which have 212,000 contract arrangements with 340B hospitals to administer medicines. That’s up from 1,700 in 2010.That kind of exponential growth is a clear tip-off that people are gaming the system.

Studies have found doctors employed by 340B hospitals are also more likely to prescribe higher-priced drugs. Why? Because the hospitals and their pharmacy partners reap bigger discounts on them than they do on generics. The result: Private insurers and Medicare spend more on drugs. This is just another example of how the increasing employment of physicians by hospitals is leading to higher healthcare costs as doctors are forced to operate under the profit-motivated rules of their employers.

As the program currently operates, a hospital can also claim the discounts for drugs administered to former patients they aren’t currently treating. Consider a privately-insured patient referred by a hospital’s primary care doctor to an outside rheumatologist. If the patient fills a medicine prescribed by that rheumatologist at one of the hospital’s contracted pharmacies, the hospital and the pharmacy can claim the discount. Hospitals and pharmacies employ firms to scour patient records and prescriptions to maximize discounts.

Hospitals are supposed to use the discounts for low-income patients, but a report this spring by Senate Republicans found little evidence they do. A study this year by consulting shop Magnolia Market Access estimated that a third of the discount dollars are directed to hospitals’ financial portfolios—bonds, stocks, etc.

Some hospitals have signed deals with minor-league and college sports teams for naming rights to stadiums. Northwell has launched a film company, supposedly to help with marketing. The discounts have also given hospitals more money to acquire physician practices. Such consolidation has increased prices and insurance premiums. In other words, more profit from hiring physicians leads to more hiring of physicians, which leads to even higher healthcare costs. This is like a freight train out of control.

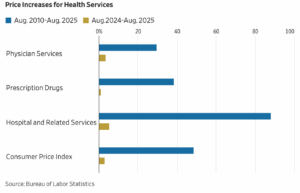

The nearby chart shows that hospital prices have increased 88% over the last 15 years, compared to 48.4% for the overall consumer-price index, 38.4% for prescription drugs and 29.5% for physician services. To offset the growing hospital discounts, drug makers raise prices.

Enter the Health and Human Services Department, which has announced an experiment to prevent hospitals from gaming the program to claim more discounts. Instead of receiving up-front discounts, hospitals would have to file claims with manufacturers for rebates, though only for the 10 drugs in the Inflation Reduction Act’s first round of price controls.

One goal is to ensure that drug makers don’t have to pay discounts twice on the same drugs. Another is to provide more transparency by requiring hospitals and pharmacies to validate the patients and prescriptions for which they are claiming discounts. The government’s current method is trust the hospitals, which want to keep it this way.

The hospital lobby last month all but threatened to sue HHS if it moves forward with its experiment. Some 166 members of Congress, mostly Democrats, demanded HHS cancel its test. It’s amusing to watch progressives like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez defend big, wealthy hospitals.

On a more constructive note, GOP Reps. Earl Carter (Ga.) and Diana Harshbarger(Tenn.) have introduced legislation that would ensure the 340B program benefits low-income hospitals and patients, as it was intended.