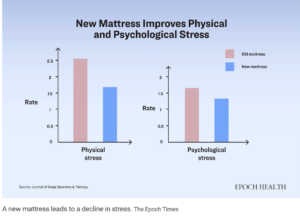

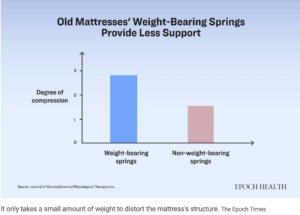

In Part I of this series, we learned that your mattress may be the source of your pains, especially in your low back. A firmer and newer mattress may be the solution.

But there are other threats to your health in your mattress. In Part II we will discuss these other threats. Flora Zhao, writing in The Epoch Times, tells us many people with unexplained symptoms simply need to replace their mattress. What are these threats?

Dust Mites and Allergens

An old mattress not only compromises support for your body, but can also lead to other problems. For example, dust mites can thrive in an old mattress. Human skin renews itself constantly, shedding an average of 1.5 grams of dead skin cells each day. This amounts to roughly 1.1 pounds of skin flakes annually, most of which become “house dust.”

The continuous shedding and accumulation of skin cells in the environment is not a problem in and of itself. The real problem is that these skin cells serve as food for dust mites. Old mattresses often harbor large populations of these mites. They are microscopic, measuring about 0.4 millimeters in length, and invisible to the naked eye. They thrive in warm, humid conditions with ample food, which means mattresses are their ideal habitat.

Dust mites carry various allergens in their droppings, exoskeletons, and eggs. More than 20 known mite-related allergens can trigger allergic reactions and contribute to the development of atopic dermatitis. One study found that approximately half of U.S. households have dust allergen levels at or above the presumed allergy sensitization level (more than 2 micrograms per gram of dust). Dust mite allergens at levels exceeding 10 micrograms per gram (µg/g) of dust are considered likely to induce allergic symptoms. A study conducted on mattresses in a dormitory for hospital staff in Thailand showed that after nine months of regular use, the average dust mite allergen level in sponge-like polyurethane mattresses increased to 11.2 µg/g of dust. After 12 months, this level had doubled.

The type of mattress can also influence dust mite density. An early study conducted by Norwegian scientists on more than 100 mattresses found that foam mattresses were about three times more likely to harbor dust mite droppings than spring mattresses, and foam mattresses without covers were five times more likely to have them. Researchers in Brazil found that dust collected from the lower surface of mattresses was significantly more infested with dust mites than the upper surface—3.5 times more.

These microorganisms can cause a range of symptoms, including headache, fatigue, chest tightness, coughing, asthma, allergies, eye and nasal irritation, rashes, and muscle pain. For individuals with weakened immune systems or chronic lung disease, bacteria can infect the lungs, potentially leading to hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Bacterial growth in mattresses has also been linked with some cases of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

Flame Retardants

Since the 1970s, regulations have mandated the addition of flame retardants to consumer products. These substances are known for their persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity. From 2004 to 2017, regulatory controls on these chemicals were gradually included in the Stockholm Convention, a global treaty that protects people from persistent organic pollutants. Today, many of the controversial flame retardants have been phased out in most countries.

However, households may still be using mattresses containing these potentially hazardous substances. Flame retardants typically constitute about 3 percent to 7 percent of the weight in polyurethane foam. Although the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission approved a petition in 2017 to stop requiring flame retardants, it will take years to eliminate these toxic substances from household environments.

A 2022 study showed that mattress covers were found to contain flame retardants despite certifications for the foam. In four newly purchased mattress covers tested by researchers, two contained more than 50 percent fiberglass—a common flame retardant used in mattresses—in the inner layers. The fiberglass fragments, ranging from 30 to 50 micrometers in diameter, could be inhaled into the nose, mouth, and throat. Some materials, like natural rubber and wool, are naturally flame-resistant. Opting for mattresses made from these materials can help minimize exposure to flame retardants.

In summary, your mattress may be the source of your back pain, your insomnia, headaches, fatigue, chest tightness, coughing, asthma, allergies, eye and nasal irritation, rashes, and muscle pain. Although mattress warranties may be for 20 years or more, replacing your mattress sooner may solve some of these problems.